Möbius - a performance lecture script from New Approaches to Counterculture at the Institute for the Advanced Study of the Humanities University of Edinburgh, 12th April 2018

This is the script for a performance lecture by Dawn Woolley and myself. The performance was intentionally disruptive and disrupted.

The film with a spoken script will be available soon...

Möbius

[TEXT] ‘[T]echnology has become the great vehicle of reification’ (Marcuse, 1964, p. 168).

[TEXT] ‘First as tragedy, then as farce’ (Marx, 1852).

[FOOTAGE FROM PROTESTS – 1960s TO PRESENT DAY - (OVERLAPPING AND BUILDING AND LOOPING) WHILST FOLLOWING TEXT IS SPOKEN]

[DAWN] ‘It … tells us something about temporality and sameness, and hence about repetition. Marx does not speak of the re-presentation of a simple presence that every so often replicates itself, but of a somewhat paradoxical return of the “same” that cannot be reduced to pure sameness. The “as such” is never such … [R]epetition involves a certain recovery that does not leave the original unchanged … [T]he possibility of alteration is inscribed in every act of recovery … If there is no alteration, instead of repetition there is only … monotony’ (Arditi, 2007, p. 137).

[STEPHEN] ‘The claim that history repeats itself therefore suggests that the original is always already exposed to an occurrence that will alter its initial sense as it redeploys itself. From drama to farce, the temporarily of repetition resembles the impossible return to origins that Escher portrays in his etchings of coils or Möbius strips, endless cycles that never close back on themselves’ (Arditi, 2007, p. 137).

[TEXT] CULTURE

[CUT FROM WAYS OF SEEING PLAYING SILENTLY WITH SUBTITLES - DAWN SPEAKS OVER]

[DAWN] In advanced capitalism the dominant or ruling classes are global corporations imposing industrially produced mass culture on the world. According to Baudrillard, mastery of accumulation through surplus-value is essential within the economic order, but in the order of signs the mastery of expenditure is fundamental. It is in this form of control that the dominant classes are able to monopolise and determine the cultural code. In capitalist society the dominant class aims to:

surpass, to transcend, and to consecrate their economic privilege in a semiotic privilege, because this later stage represents the ultimate stage of domination. This logic, which comes to relay class logic and which is no longer defined by ownership of the means of production but by the mastery of the process of signification (Baudrillard, 1981, pp. 115-6).

Determining what is valued by society, and what constitutes culture is the ultimate stage of domination.

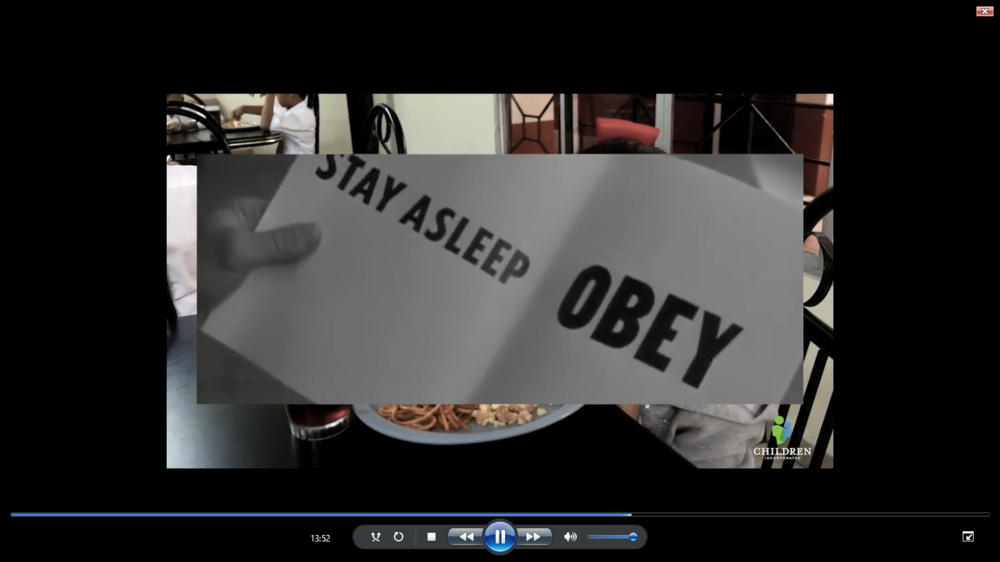

[STEPHEN] Utopia sustains the domination of our political and economic systems. There is no alternative. Neoliberal utopian totality has all but smothered subversive utopianism under intricate webs of exploitation and reification that serve to turn people into little more than ‘obedient automatons’ (Moylan, 1986, p. 16). Society has become a ‘seamless web of media technology, multinational corporations, and international bureaucratic control’ (Jameson, 1982, p. 92). The state and civil society maintain a ‘totally administered society’ in which the soft power of the latter masks the hard power of the former (Moylan, 1986, pp. 16-7). Technocracy enforces total administration within physical and digital communities locally, nationally, globally and transnationally.

[DAWN] Culture, in particular the visual arts are forms of semiotic privilege that produce and enforce sign-value domination. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Benjamin, 2008 (1936)), Walter Benjamin says the authority and authenticity of a work of art ‘represents an important cultural substantiation of the claims to power of the dominant class’ (Benjamin, 2008, p. 15). Because the bourgeoisie have monopolised the modes of artistic production, they also control the aspects of culture that determines meaning and value for society. This is used to justify and reinforce their position while simultaneously preventing dissent. In the nineteenth century, art and technology production processes developed rapidly. According to Benjamin, the working-classes could have harnessed the new media for revolutionary purposes but instead the potential was used in the service of capitalism because the bourgeoisie controlled their methods of production.

Culture is located in art galleries, theatres, music shops, newspapers and magazines – everywhere, even billboards. But all these locations are reproduced on social networking sites, they allow cultural values to be disseminated and propagated on a massive scale. Because we are producers and consumers online, social networking sites are both factory production-line and shop floor for social and cultural values. Like the modes of production described by Benjamin, social networking sites hold revolutionary potential, but only if the masses take ownership of them. And at this moment in time, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are being rapidly and aggressively colonised by commerce.

I have come to view social networking sites are the contemporary commercial space where commodity culture pervades social existence. They capitalise on our need for community inclusion and desire for prestige that can be gained from association with prominent social members, making them prime sites for commercial exploitation.

[TEXT] “COUNTERCULTURE”

[CUT FROM SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE WITH SUBTITLES – STEPHEN SPEAKS OVER]

[STEPHEN] Yet it is unproductive to simply denounce commodification and consumer culture. It is necessary to critique capitalism as the producer of consumer society (Kellner, 1983, p. 78). Commodity culture has colonised everyday life. The ‘same trend of production and consumption, which makes for the affluence and attraction of advanced capitalism, makes for the perpetuation of the struggle for existence, for the increasing necessity to produce and consume the non-necessary’ (Marcuse, 1969, p. 38).

And, whilst the counterrevolution of the free-markets has ‘invaded … rebellion and made it a business’, social movements continue to self-organise and oppose what appears to be, as Herbert Marcuse points out, ‘a functioning, prosperous, "democratic" society’. Such movements work to expose, often on moral grounds, the ‘hypocritical, aggressive values and goals’, the ‘blasphemous religion’ of capitalism and the falsity of a society that destroys the very things it claims to support and believe in (Marcuse, 1969, pp. 44-5).

[DAWN] For a short time, I created selfies and shared them online. I tagged my photographs with the word ‘selfie’ and looked at the collection of bodies and faces given equivalence through this shared categorisation. I discovered that many followers on Twitter are individuals who conceal that they are acting on behalf of commercial enterprises. They search under the selfie hashtag to target individuals with fashion, fitness programmes, and cosmetic treatments, claiming to help them achieve an ideal look. I was surprised to find photographs representing a wide variety of commodities, from make-up to balls of wool, also marked with this hashtag.

The term selfie is used to advertise self-improvement products, suggesting there is no distinction between the commodity and the body that uses it: they are one object. The advertisers address me in a way I have not experienced before, implying the commodities are already assimilated to my identity before I make a purchase. The mode of identification is direct and forceful – the commodity is you and you are it; there is no escape from this consumer relation. The browser window that displays my body also displays commodities I can use to increase my value as a commodity. The repetitive layout of images on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook reinforces equivalence between body and commodity, obliterating the hierarchy between consumer and consumed.

Social networks are equivalent to nineteenth century factories – spaces in which value and culture is produced and reproduced and therefore the site of struggle over who controls the modes of production.

[STEPHEN] Schmidt noted that Lefebvre’s concept of ‘the production of space’ – social space as a social product - was an essential part of social reality; an inherently materialist theory of space in which space and time are not universal but contextual, relational and historical (2008, pp. 28-9). Space can thus be conceived of as being continually produced and reproduced; an active, complex network of relationships situated within time. Within technocratic neoliberal spaces, bureaucracies, technologies and free-markets are purportedly ‘morally neutral’. Yet neoliberal institutions are ‘social products, shaped by social forces and shaping the behavior of their peers’ (Feenberg, 2014, p. viii). They produce, destroy and reproduce reified spaces and reified societies. Reification has colonised everyday life and our ‘oppositional consciousness’ to such an extent that there is, today, almost no escape from the propaganda of consumerism (Feenberg, 2014, p. ix).

[DAWN] In capitalist societies, each person acts as an individual consumer in pursuit of enjoyment and as an individual worker selling her/ his labour in competition with others. Capitalism binds individual subjects through incorporation and assimilation rather than domination: ‘capitalism […] constantly decodes or pulls apart existing social codes, and integrates anything that deviates from existing codes into the system of capitalism to produce new markets’ (Bryant, 2008, p. 9). Capitalism uses differences as opportunities for growth. Developing new marketplaces in social networking sites are examples of the process of incorporation and extension that characterise capitalist growth.

[TEXT] RECUPERATION

[STEPHEN] Neoliberalism is both cultural and countercultural. And capitalist growth is founded upon innovation. Innovation is neoliberal: political and economic. In art today, innovation is the production and reproduction of novelty, consumption and capital. Schumpeter was the originator of creative destruction and of the notion of entrepreneurial innovations as key drivers of economic growth; the father (or one of the fathers) of neoliberalism. Disruptive innovation and creative destruction underpin free markets (Heath, 2015).

For John Berger:

Publicity is the life of this culture – in so far as without publicity capitalism could not survive – and at the same time publicity is its dream. Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their own interests as narrowly as possible. This was once achieved by extensive depravation. Today in the developed countries it is being achieved by imposing a false standard of what is and what is not desirable (Berger, 1972, p. 154).

Of course, the spectacle creates contested spaces of ‘political opposition and resistance’ and ‘domination and hegemony’ (Kellner, 2012, p. xvii). Spectacular spaces therefore offer both the reality of exploitation and oppression and the possibility of hope and liberation.

For Lefebvre, fetishising the ‘formal “signifier-signified” relationship’ contributes to the passive acceptance of the ‘ideology of organised consumption’ which, like ‘“real” consumption’, is also a consumption of signs. It adds to ‘the consumption of “pure” spectacles, superimposing itself ‘as a determination’. This process drives the advertisement of consumer products as the ‘principal means of consumption’ using art, literature and poetry as little more than rhetorical devices. The ‘reality’ and the ‘image’ are split so that both object and sign are consumed. The production of signs becomes increasingly important to ‘other productive and organizing social activities’: ‘The sign is bought and sold; language becomes exchange value.’ The signified becomes consumption. When sites – and this, we argue, applies to the digital as well as the material – become ‘signs and values’ and ‘formal significations’, the receivers of these signs become ‘pure’ consumers (Lefebvre, 1996, p. 115).

[TEXT] INTERVENTION

[STEPHEN] Consumerism has reduced utopianism to ‘the consumption of pleasurable weekends, Christmas dreams, and goods purchased weekly in the pleasure-dome shopping malls’; simultaneously defining anything outside these ‘commodity-defined needs’ as ‘psychologically or socially aberrant’. Yet countercultures constantly revive a sense of ‘the not yet realized potential of … human community’. The oppositional critiques of ‘critical utopias’ express both an acceptance of the limits of utopianism as whilst accepting the dream of utopia. Blueprints are replaced by the ‘rejection of hierarchy and domination’ and oppositional visions ‘deeply infused with the politics of autonomy, democratic socialism, ecology, and especially feminism’. Nevertheless, for many today, conscious and unconscious utopian desires have been ensnared by crass consumerism (Moylan, 1986, pp. 8-16).

The only way to is to take back the social – in both physical and digital senses. For David Harvey, the ‘inequality, alienation and injustice’ produced by neoliberalism must be challenged by demands and, if necessary, conflict. Justice is ‘not a gift’ but rather it must be ‘seized by political movement’ (Harvey, 2009, pp. 45-9).

[DAWN] In Surrealism: Snapshot of the Last European Intelligentsia Benjamin says revolutionaries have a double task: 'to overthrow the intellectual predominance of the bourgeoisie and to make contact with the proletarian masses'.

In my work, I am interested in how images are consumed, particularly how ideology is transmitted through commercial visual culture. To research this process, I produce site-specific art works for commercial advertising spaces on billboards and social networking sites. It is my intention to present images that disrupt the repetitious order of consumerism, creating a space in which the viewer can critically consider advertising and some of the contradictions of capitalist consumption.

To explore and emphasise the ideological messages of commodities I scan products and post them on instagram as a ‘wish image’ with hashtags that reveal the commodities’ signifying message (Woolley, 2015-18). The title of this work Wishbook derives from nineteenth century commodity catalogues such as The Great Wish Book and American Dream Book, selling the American way of life and a homogenised version of culture. The title also alludes to Benjamin’s idea that consumers can appropriate commodities as emancipatory wish images. In The Arcades Project (1999 (1927-40)), (Benjamin, 1991, pp. 115-7). Buck-Morss describes Benjamin's idea of the wish image:

if the social value (hence the meaning) of commodities is their price, this does not prevent them from being appropriated by consumers as wish images within the emblem books of their private dreamworld. […] once the initial hollowing out of meaning has occurred and a new signification has been arbitrarily inserted into it, this meaning ‘can at any time be removed in favor of any other (1991, pp. 181-2).

[STEPHEN SPEAKS OVER DAWN]

[DAWN] Consumers can reject the social values given to objects and give them different meaning. The consumer then becomes a producer of culture, disrupting the semiotic privilege of the capitalism.

[STEPHEN] For Lukács, all forms of reification are based upon commodity exchange (Feenberg, 2014, p. 70). People become objects in the eyes of capitalism. Crucially, for Feenberg:

Human action in modern societies … continually constructs reified social objects out of the underlying human relations on which it is based. The reified form of objectivity of these objects gives a measure of its stability and control while at the same time sacrificing significant dimensions of the human lives they structure (2014, p. 118).

[DAWN SPEAKS OVER STEPHEN]

[STEPHEN] There are clear implications for today’s post-digital societies: for the blurry human interactions on both social media and in their ‘real’ lives.

[DAWN] My Wishbook images look like poor quality adverts or the content of a bin and the hashtags read like bad poetry. They appear among adverts on social networking sites and behave abnormally. On Instagram, I use hashtags to reach a varied audience. Each image is tagged with text such as brand names and advertising slogans that are usually associated with the promotion of the product, and with statements that challenge or contradict the dominant messages associated with the products.

[STEPHEN SPEAKS OVER DAWN]

[DAWN] The two-way communication of liking, sharing and commenting enables me to gauge the reception of my images.

[STEPHEN] Big Data makes us predictable. It ushers in ‘the end of the person who possesses free will’ (Han, 2017, p. 12). We are devoted to social media. We submit to it; obey it. The psychopolitics of neoliberalism today has trapped us in an ever-shrinking space of technological domination:

Like is the digital Amen. When we click, Like, we are bowing down to the order of domination. The smartphone is not just an effective surveillance apparatus; it is also a mobile confessional. Facebook is the church – the global synagogue … of the Digital (Han, 2017, p. 12 (author's italics)).

[DAWN SPEAKS OVER STEPHEN]

[STEPHEN] Share. Follow. Like. ‘Neoliberalism is the capitalism of “Like”’ (Han, 2017, p. 15 (author's italics)).

[DAWN] Working on Instagram also gives me insight into the way companies promote their products on social networking sites. A company will engage with a post that mentions their own products but will also comment on posts that reference products tangentially linked to theirs.

[STEPHEN SPEAKS OVER DAWN]

[DAWN] As I observe the interactions my Wishbook project receives, I begin to understand how hashtags are used to identify potential consumers.

[STEPHEN] Capitalism has become our God and Goddess. For Benjamin, capitalism is a new religion: “a cult that creates guilt” but never “atonement” – a religion of self-perpetuating, universal guilt (Benjamin, 1996, p. 288).

[DAWN] My site-specific works online also employ the same tactics used by commodity producers to hone my posts to more accurately target my audience. In an ongoing performance art work, I embody the voices of anti-ageing adverts through a character called The Mystical Scientist who communicates her research and promotes anti-ageing products via Twitter. Although The Mystical Scientist reproduces and disseminates information about anti-ageing products, her language is ambiguous and occasionally critical. She infiltrates a consumer demographic on Twitter and acts abnormally.

She follows and is followed by anti-ageing scientists, cosmetic producers, fitness instructors, and diet plan representatives. In my attempt to simultaneously mimic and critique the anti-ageing advertisers and commodity producers, I am able to observe the characteristics of other twitter users who predominantly use their account to promote anti-ageing products. I learn from the methods of capitalism to produce art works that critique capitalism, but in the process, I come to resemble a capitalist. I am assimilated and incorporated by the system.

[STEPHEN] Brian Holmes described this feeling of being incorporated within global capitalist hegemony as reflective of the ‘lived experience of a relation of domination’ in which people develop ‘the flexible personality’ (2007 [2004], p. 353). Yet it is, perhaps, possible to use the ‘dialectics of art’ – the simultaneously positive and negative – to stabilise and subvert artistic practice by analysing its social and political contexts; by becoming simultaneously ‘conformist and oppositional’. This cannot create freedom, but rather ‘the preconditions for a free society’ (Kellner, 1984, pp. 360-2). Herein lies possibilities.

Perhaps our hopes and dreams are alive in the critical utopias of today and tomorrow? In spaces, like social media, in which process is emphasised, not systems; where the marginal replaces the central; in which disobedience and autonomy replace order and control; and in which liberation for all people replaces white, male, middle-class dominance.

[DAWN SPEAKS OVER STEPHEN]

[DAWN] ‘Marx does not speak of the re-presentation of a simple presence that every so often replicates itself…’

[STEPHEN] For Marcuse, the dismantling of what we now call our neoliberal society could take two routes: the ‘Great Refusal’ or the ‘Long March’. Rejection is not an option today. Instead, we must become part of the institutions which exploit and oppress us (Feenberg, 2014, p. 220).

[DAWN SPEAKS OVER STEPHEN]

[DAWN] ‘… but of a somewhat paradoxical return of the “same” that cannot be reduced to pure sameness…’

[STEPHEN] We must ‘take seriously consumer politics and consider participation in new social movements, like the consumer, health, environmental movements’ because only in so doing can we make radically progressive changes. Our work can produce ‘New critical theories of consumption’ which ‘begin as “anticipatory prefigurations” of a new society, as each of us begins more consciously and socially to develop consumer practices aimed at the elimination of all commodities and consumer activities that are not genuinely useful, beneficial and life-enhancing’ (Kellner, 1983, pp. 79-80).

[DAWN AND STEPHEN] ‘The “as such” is never such’ (Arditi, 2007, p. 137).

[DAWN AND STEPHEN] ‘The “[RECITE FROM MOBIUS STRIPS]” is never such’ [CHANGE EACH TIME. REPEAT. SPEAK OVER EACH OTHER.]

[END]

Bibliography

Arditi, B., 2007. Politics on the Edges of Liberalism: Difference, Populism, Revolution, Agitation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Baudrillard, J., 1981. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. USA: Telos Press.

Benjamin, W., 1991. Quoted in Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Benjamin, W., 1996. Capitalism as Religion. In: M. Bullock & M. W. Jennings, eds. Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1913-1926. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 288-91.

Benjamin, W., 1999 (1927-40). The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Benjamin, W., 2008 (1936). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London: Penguin.

Benjamin, W., 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Berger, J., 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin.

Bryant, L. R., 2008. Žižek’s New Universe of Discourse: Politics and the Discourse of the Capitalist. International Journal of Žižek Studies, 2(4).

Buck-Morss, S., 1991. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Debord, G., 1967. The Society of the Spectacle. Black & Red ed. Oakland: AK Press.

Elliott, J. E., 1980. Marx and Schumpeter on Capitalism's Creative Destruction: A Comparative Restatement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 95(1), pp. 45-68.

Feenberg, A., 2014. The Philosophy of Praxis: Marx, Lukács and The Frankfurt School. Revised ed. London and New York: Verso.

Han, B.-C., 2017. Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. London: Verso.

Heath, J., 2015. Methodological Individualism. In: E. N. Zalta, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition). Online ed. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Holmes, B., 2007 [2004]. The Revenge of the Concept: Artistic Exchanges, Networked Resistance. In: W. Bradley & C. Esche, eds. Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader. London: Tate Publishing, 2007.

Jameson, F., 1982. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kellner, D., 1983. Critical Theory, Commodities and the Consumer Society. Theory, Culture and Society, 1(3), pp. 66-83.

Kellner, D., 1984. Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism. Basingstoke and London: MacMillan.

Kellner, D., 2012. Media Spectacle and Insurrection, 2011: From the Arab Uprisings to Occupy Everywhere. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lefebvre, H., 1991 [1947]. Critique of Everyday Life Volume 1: Introduction. London: Verso.

Lefebvre, H., 1996. Right to the City. In: E. Kofman & E. Lebas, eds. Writings on Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

Marcuse, H., 1964. One-Dimensional Man. Boston: Beacon Press.

Marcuse, H., 1969. An Essay on Liberation. [Online]

Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/marcuse/works/1969/essay-liberation.pdf

[Accessed 16th July 2015].

Marx, K., 1852. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. [Online]

Available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm

[Accessed 27th March 2018].

Moylan, T., 1986. Demand the Impossible: Science fiction and the utopian imagination. New York and London: Methuen.

Schmid, C., 2008. Henri Lefebvre's theory of the production of space: Towards a three-dimensional dialectic. In: S. Kipfer, K. Goodewardena, C. Schmid & R. Milgrom, eds. Space, Difference, Everyday Life: Reading Henri Lefebvre. New York and Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 27-45.

Simon, H., 2001. Quoted in Thomas H. Davenport and John C. Beck, The Attention Economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Woolley, D., 2015-18. Wishbook. [Art].