More Today Than Yesterday (But Less Than There'll Be Tomorrow)

This is the transcript from my keynote speech at Nuart Festival in Stavanger on 8th September 2019. It explores nostalgia narratives in Street Art and examines the practice’s links to gentrification. But perhaps we’re all gentrifiers nowadays?

The full article on which this talk was based is available in Nuart Journal III and can be downloaded for free here.

MORE TODAY THAN YESTERDAY (BUT LESS THAN THERE’LL BE TOMORROW)

It was the art scene that filled the freshly emptied apartments, cleaned up the area, and began its transformation into the hip (and expensive) Lower East Side of today (Hornung, 2014).

If there’s one word that long been associated with gentrification, it is Bohemia. This once mythical place where counter-cultural movements loafed into existence has morphed and multiplied into a tag slapped on anywhere awaiting gentrification, anywhere “arty”, anywhere where students live, anywhere cool, trendy.

But were the ‘Old Bohemias’ really that different to those of today: the ‘New Bohemias’? Perhaps not. Bohemias have always been linked to both poverty and gentrification. Bohemias have always been the haunt of artists, artisans and the fashionable. Bohemias have always been associated with capitalism. Yet there has been a distinct shift from the Old Bohemias to the New Bohemias. This shift is undoubtedly linked to the intensification of capitalism: to property speculation, property development, urban planning, city branding, placemaking, entrepreneurialism, fashion, taste, style, creativity, the Creative City and the Creative Class. ‘Accumulation by dispossession’ doesn’t care about existing communities, families and people – particularly those from the lower-classes or in poverty. Capitalism at its most primitive is about theft of value, of meaning, of everything exploitable. However, whereas many Old Bohemians were blissfully unaware of their role as pre-gentrifiers, today’s New Bohemians willingly embrace their role as the meanwhile inhabitants of these temporal outposts. Nonetheless, the path from Old Bohemias to New Bohemias reveals how gentrification became a global phenomenon and how artists, writers, other creative types, students and hipsters became essential cogs in the well-greased wheels of global capitalism (Pritchard, 2018).

So what does street art have to do with this? Well, street art is an essential part of the Creative Class narrative. Every city has ‘up-and-coming’ areas clad from shop shutters to back alleys, sides of dilapidated buildings to shifty-looking subways, in what has become known as street art. Street art is a certain type of graffiti which today has come to be synonymous with murals that often claims to be ‘unauthorised’ but is frequently part of the gentrification cycle.

Abarca points out how small-scale, unauthorised and transient street art has been subsumed by the juggernaut of corporate street art, frequently adopting muralism as its primary form, arguing that ‘there are clear and fundamental differences between the smaller, unsanctioned works we used to call street art in the past decade and the huge institutional murals of today’ (2016, p. 60). However. whilst these differences are clear, it is still possible that at least some of the ‘smaller’ street art works of the past have been implicated in the rise of street art as a global city branding phenomenon.

The practice is steeped in the type of mythology that commonly masks a cultural secret: one in which the establishment recuperation of a once working-class cultural activity is hidden behind a false counter- or sub-cultural veneer that is on the one hand cynical postmodern pastiche and on the other, a sinister form of neoliberal cultural warfare. I will not list examples here, for they are legion. The purpose here is to explore an example of how what I term ‘proto-street artists’ attempted to adopt the ‘native’ street cultures of New York’s Lower East Side in the 1970s and 1980s in an earnest attempt to fight gentrification of the area but ended up signposting the practice and its ‘gritty’ street aesthetic to the art world, to property developers, to the media, to the fashion world, and, indeed, to local and national governments and their agencies.

There is a nostalgia narrative attached to street art and it is directly connected to gentrification (Ocejo, 2011). Early gentrifiers use nostalgia narratives reconstruct the past lives of people and places using a sense of loss to create new identities that utilise a very specific interpretation of ‘loss’ to appear to oppose and challenge later waves of gentrifiers which may threaten to displace these ‘urban pioneers’.

Nostalgia narratives are a form of ‘collective memories’, invented to create new identities and new ‘traditions’ (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983). These narratives weave new-found ‘personal experiences’ into an area’s supposedly ‘gritty past, ethnic and cultural diversity, and creativity and creative production’ which are mythologised as ‘authentic’ (Ocejo, 2011, p. 286). Clearly, street art (like many other forms of cultural practice) frequently uses nostalgia narratives to create the impression of a ‘movement’. Yet it is a false impression. Of course, artwashing also utilised nostalgia narratives to sanitise, repackage and sell areas’ ‘dangerous’ and ‘grim’ pasts to later waves of gentrifiers as a form of sentimental and nostalgic ‘memory’. To do this is to ‘museumify’ the lives of those who have already been and are being continually dispossessed of their ways of being and living and displaced from the places they once called home (Pritchard, 2017).

The trouble with street art today is that it is neither an ‘emerging’ nor a ‘young’ practice, and it is certainly not anti-establishment or anti-gentrification. Rather, it is a pernicious form of artwashing that functions both at the frontiers of gentrification and at every stage that follows as it becomes an essential means to cement the newly ‘creative’ neighbourhoods’ statuses, alongside a raft of other establishment-sanctioned ‘creative’ and ‘cultural’ activities (Schacter, 2014). Street art has become part of the almost ubiquitous Creative City branding employed by ‘creative’ cities everywhere. Schacter describes how street art has been ‘co-opted, artistically annexed, through acting as a (literal and metaphorical) facade, a mere marketing tool for the Creative City brand’ (2014, p. 162).

Street art, unlike graffiti, is part of the art world. It is part of neoliberalism. It is a part of the globalisation of our planet and its cultures with a homogenous aesthetic that is neither challenging nor subversive. Quite the opposite, I argue. Street art has its museums in chic global capital cities. Street art has its tours in almost every city across the globe. Street art is everywhere in advertising and fashion. Street art sells for big money. Street art sells property. Street art sells people with the least down the river – dispossessing and displacing them in favour of the ‘cool’, ‘hip’ and ‘arty’ types it intentionally seeks to attract. Street art is about the ‘shareable’, consumerist Instagram aesthetic, not social justice. Street art sells the city. It does not take it back.

The practice has been described as ‘far and away the world’s most globally accessible genre of contemporary art’ (Rea, 2019). There is, of course, an increasingly critical discourse developing within the street art community and some artists are attempting to respond critically to the practice’s co-optation (Hansen, 2015; Abarca, 2016; Reed, 2018).

Just think about why street art and street artists have come to represent the respectable, ‘cheeky’ and ‘non-conformist’ aspects of urban existence, particularly in gentrifying and gentrified areas in Creative Cities. Think about why street art draws a particular group of people – the Creative Class – to cities and to gentrified and gentrifying areas. Think about the tags and working-class graffiti that is, unlike street art, deemed to be ‘vandalism’, ‘criminal’ and ‘anti-social behaviour’. Vandalism is a cultural practice, just as street art is. However, the two practices are very different.

One of my favourite works of ‘art’ (and perhaps ‘anti-art’) is the commissioned street art mural in East London featuring a lap dog. It was not long before the Giant Chihuahua painted by street artists Boe and Irony on the side of Kilmore House in the gentrification battleground of Chrisp Street in Poplar was ‘vandalised’ to great outcry with the word, ‘GENTRIFIED’ and a ticked box. It is possible that some might consider this addition as ‘street art’ as an ‘aesthetic protest’ (Hansen, 2015), but this is not, for me, the case. Rather, it is an act of anti-gentrification activism.

Nevertheless, this piece of street art was acclaimed for demonstrating ‘just what an impact well curated street art can make to an area’ and praised for the way it transformed ‘the place from something quite hard edged to something a little warmer’ (Inspiring City, 2014). Little wonder then that the media has likened London’s East End to New York’s Lower East Side, with visitors and potential gentrifiers advised to ‘Keep an eye out for the incredible street art in the area: the walls of most buildings are adorned with priceless graffiti and murals, including some by famously elusive street artist Banksy’ (Polland, 2012).

Just as the ongoing gentrification of the East End of London is being extensively documented at the moment, the gentrification of the Lower East Side area of New York has also been extensively documented for a long period, as has the role art played in the process. Yet the ‘revitalisation’ of the area represented only one phase in New York’s long history of gentrification. A process that historically placed artists consistently at its forefront and consistently displaced them. For Sharon Zukin, New York was unique: ‘a prototype free-market experiment’ that created ‘cultural districts’ which attracted communities of artists at relatively little cost.

The city’s first Bohemian district was Greenwich Village which had a history of artist inhabitation that went back to the late-nineteenth century, but rent rises in the 1950s and 1960s forced most artists to migrate to other areas of Lower Manhattan.[1] SoHo became the next Bohemia, but gentrification there led artists to move to the Lower East Side (or East Village as it became known) in the late-1970s and early-1980s. The area became internationally recognised for its art scene by the mid-1980s and this in turn led to gentrification that forced artists to migrate first to Williamsburg, then, in the twenty-first century, to East Williamsburg and finally to Bushwick (Zukin, 2011, pp. 25-9).[2]

The Lower East Side is interesting because, not only did it become a mecca for artists in the 1970s and 1980s, it also was site of experiments in live/ work spaces for artists. The area had been virtually cut off by banks – ‘redlined’ - before suddenly, in the 1980s, becoming a site of intensive speculative financial investment due to its re-designation as a ‘greenlined’ zone: a profitable ‘new urban frontier’ (Smith, 1996, p. 22).

And, just as the commodification of art quickened during the 1980s, so did neoliberalism and gentrification. Culture and politics also became aestheticised; underground and sub-cultures were speedily commodified and appropriated by mainstream commercial interests.[3] In Lower East Side, art galleries played the central role, acting as brokers for new ‘grassroots’ artists and the international art world alike (Smith, 1996, pp. 17-8). Nevertheless, some artists attempted to resist the forces of East Village gentrification.

Artist Lucy Lippard conceived of the artist-led collective Political Art Documentation and Distribution (PAD/D) in 1979. It sought alternatives for artists outside of the mainstream art establishment. Its main objective was ‘to provide artists with an organized relationship to society’.[4]

Founding member Gregory Sholette described the area’s diverse cultural mix and decaying buildings as ‘enduringly vital’, fondly painting a picture of the area as resembling ‘a B-movie version of life amidst the ruins of a nuclear or environmental catastrophe’.[5] For Sholette, this ‘vitality’ had a mongrel nature: ‘part living, part mineralized ruin, part text but always more authentically “natural” than the genteel communities of either SoHo or Nassau County’.[6] Whilst he accepted that artists were ‘immigrants’ to the area and had played a central role in the displacement process that had accompanied its gentrification, he seemed drawn to Lower East Side’s ‘anarcho-apocalyptic mix’.

Yet he also drew a distinction between himself and the ‘new wave of young immigrants’ who were ‘willing to forego bourgeois comforts and even risk their safety in pursuit of three goals: cheap rent, discovery in the traditional manner by a patron … and … contact with something “authentic” such as the imagined organic quality of other people’s (ethnic) communities’ (Sholette, 1997).[7]

Instead, Sholette aligned himself with political art activists and became a key figure in PAD/D. The collective took part in demonstrations, held meetings and events, formed committees and created exhibitions, insisting upon the political nature of all art; seeking to explore how artists might become aligned with ‘cultural activists’. Sholette described PAD/D’s aesthetic as ‘carnivalesque’ (Morgan, 2014). Nevertheless, it is difficult not to perceive of a sense of romanticism, of adventure – nostalgia even - in the work of PAD/D, and particularly Sholette.[8]

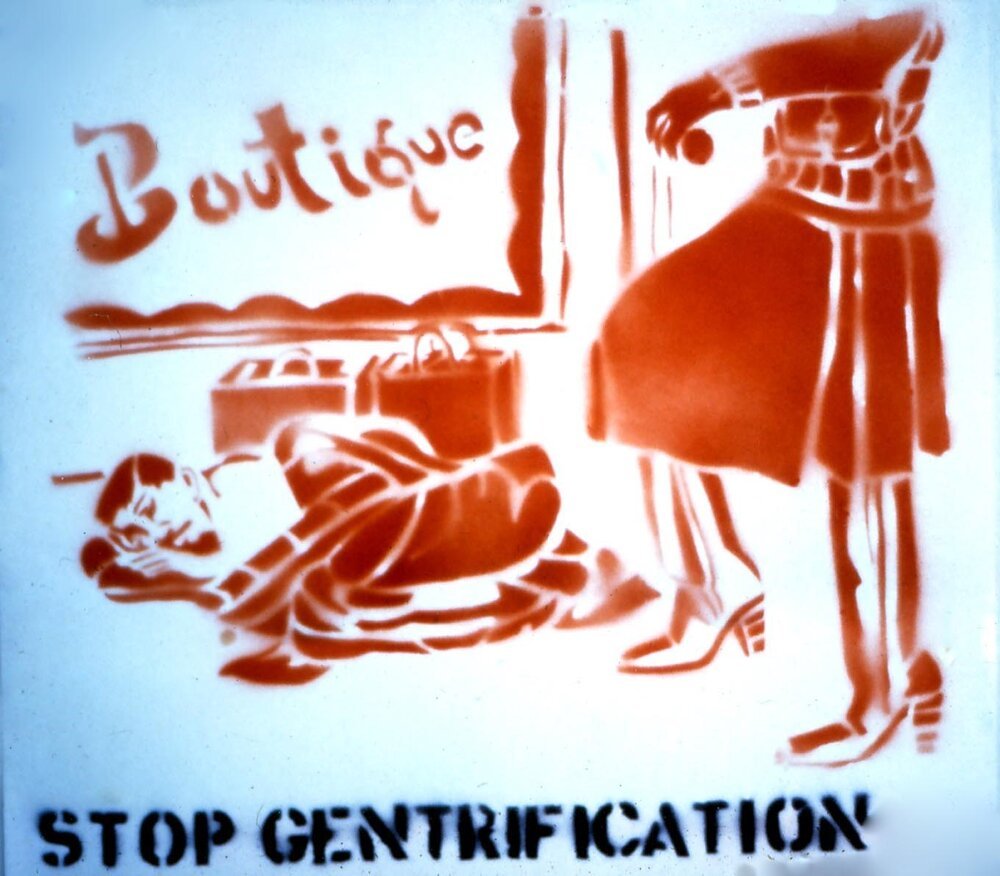

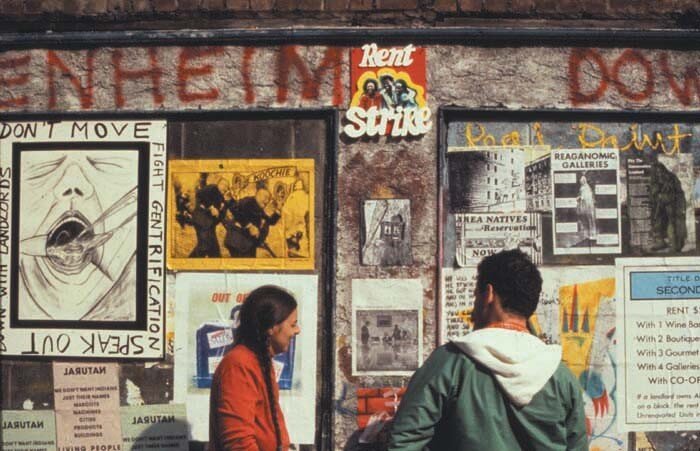

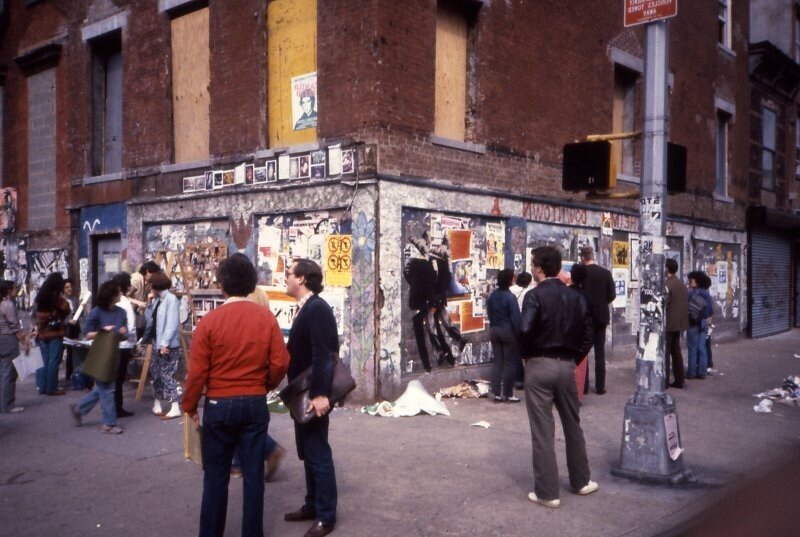

Sholette described how PAD/D artists satirised what he called ‘the naturalizing language of the real estate industry’ which was used in the marketing and advertisements of developers, financial speculators and city authorities to decry the area as ‘“untamed territories” where upwardly mobile white renters were called upon to serve as “trail blazers” or “urban pioneers”’. The artists primarily presented their work outdoors – in ‘“street” settings’ - frequently using abandoned buildings as part of their attempt to contest an ‘environment of licit and illicit visual chaos’ in which ‘wheatpasted hand bills, commercial advertising, signage from retail businesses, fluorescent graffiti, stencils, murals and posters, some of which also presented anti-gentrification messages to the public’, vied for prominence.

For Sholette, PAD/D’s ‘oppositional art’ was an attempt to counter dominant representations of the neighbourhood by naturalising it as ‘difference’ or ‘a lost plenitude’ by engaging with ‘the social and economic plight of the inner city’ (1997). PAD/D’s Not For Sale: A Project Against Displacement (1983) was held in a disused school turned community centre which was also PAD/D’s home (Sholette, 2014, p. 10). Sholette described its format as ‘traditional’ (1997) and the exhibition opening as follows:

Punk bands, guerrilla theater and activist rabble-rousers accompanied the opening while throughout the night, teams of stencil artists took to the streets armed with spray paint and anti-gentrification imagery. Additional video and cabaret presentations took place at the Millennium Film Theater and neighborhood ‘art bars’ including the Wow Cafe and Limbo Lounge (2014, p. 10).[9]

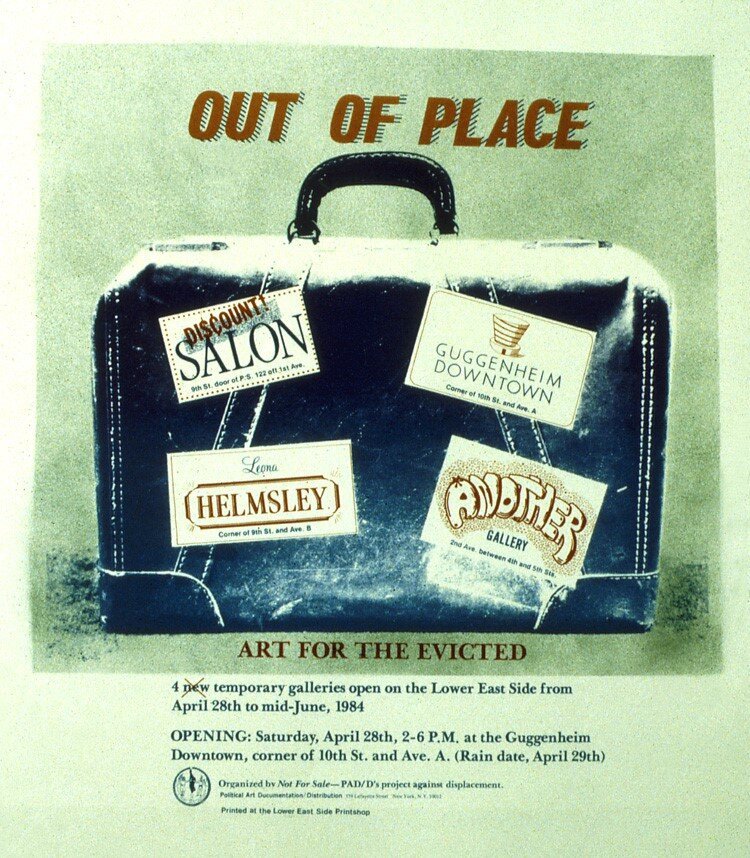

The intention was to encourage artists in the community to ‘try and assert something against gentrification’ (Sholette, 2016b). PAD/D’s next exhibition in 1984 was a ‘parodic street project’, Not For Sale: Art For The Evicted. It designated four street locations in the East Village as ‘art galleries’. Each was given a spoof name which was spray-painted onto each site. The names - ‘The Discount Salon’, ‘The Leona Helmsley Gallery’, ‘Another Gallery’, and ‘Guggenheim Downtown’ - consciously parodied New York art and gentrification (Sholette, 1997).[10] Yet the names and designation of derelict sites as mock art galleries can also be read as a nod towards familiar arts establishment practices, including hosting an opening event replete with refreshments.

Contributing artists were each asked to provide twenty copies of an anti-gentrification poster which would be continually pasted onto each of the exhibition’s four mock venues and in other street locations (Sholette, 2014, p. 10). The second exhibition, like the first, targeted East Village art galleries and its art community with the intention of raising their awareness about gentrification in the area (Sholette, 2016a).

The Not For Sale group disbanded after the exhibition, dispirited by the area’s intensifying gentrification as well as by the lack of interest in their work by the wider local art community. Sholette said soon after the decision to disband that the group were ‘the nemesis of the East Village scene – in a simplified form, unfortunately’. He asked prophetically: ‘The question is, how does it go beyond just the art world? That’s the tough part’ (Garber, 1984, pp. 14-6). This was a question that Sholette would wrestle with throughout his career.[11] Nevertheless, it seems clear that PAD/D’s anti-gentrification actions were hamstrung by the group’s tight affinity to the very art world it had attempted to resist by representing it in an alternative form – in a form of proto-street art. Its work was, perhaps, grounded too deeply in contemporary political art to be accessible to many Lower East Side residents.

The Lower East Side was also site for large-scale commercial gentrification during the 1980s.[12] New businesses and customers attracted to the area placed pressure on the neighbourhood’s ‘earlier gentrifiers’, including some PAD/D members. They reacted, I argue, by constructing a ‘nostalgia narrative’ that enabled them to differentiate themselves from the artists and art galleries, new bars and music scenes, etc. that came during the early 1980s (Ocejo, 2011, p. 285). This is evident in Sholette’s detailed explanation of his earlier immigration to the area as his family attempted to escape gentrification elsewhere, his poetic descriptions of the area as dangerous, decayed and diverse, his critique of the newly encroaching mainstream art establishments and newer artist immigrants, his emphasis on the importance of the strength and vitality of the original local community, his desire to understand the social and political situations driving the gentrification of the area, and his wish to use art to highlight the threats posed by later waves of gentrifiers.

For sociologist Richard E. Ocejo, early gentrifiers tended to ‘weave their commitment to the slum into their narrative and … new local identity’, believing their subsequent involvement in ‘community activism’ helped ‘prevent the neighborhood’s total decline’. However, unlike Ocejo’s analysis that ‘the Lower East Side’s early gentrifiers do not mention the unintended consequences of their efforts’ (2011, pp. 292-3), PAD/D members made their role in the gentrification process explicitly clear, even if they were uncomfortable with it. Nevertheless, Sholette, for example, clearly utilised a nostalgia narrative by incorporating East Village’s socio-cultural conditions. Following Ocejo, I argue he wove his ‘personal experiences with existing residents, local characters, and local places with their experiences and contributions to its creativity’ to claim an ‘authentic’ connection to the neighbourhood and forge a ‘new local identity’ as one of the area’s ‘symbolic owners’ (2011, pp. 293-7).

Like Ocejo’s depiction of early East Village gentrifiers, Sholette also utilised the freedom provided by the general neglect of the area to pursue artistic interventions in public spaces and empty buildings. Similarly, PAD/D’s ‘carnivalesque’ street aesthetic appears to have reflected the typical focus of early gentrifier artists on ‘the urban detritus of a neglected downtown’ to create the illusion of a singular, continuous mode of cultural production, linked directly to social and environmental conditions (Martinez, 2010, p. 18; Ocejo, 2011, p. 297).[13]

Sholette also suggested that later influxes of artists and audiences failed to understand the uniqueness of the East Village’s art, space, diversity and creativity (Sholette, 2016a) – echoing sociologists Miranda Martinez and Ocejo. Crucially, I argue that Sholette’s depiction of PAD/D’s mediating role in Lower East Side reflected the early gentrifier’s function there as ‘mediators between the neighborhood and city government through the community board and local groups’ and their desire to try to ‘shift the neighborhood in a particular direction that is influenced by the harms and threats that they experience from social and cultural displacement’.

This reliance upon a nostalgia narrative is, however, both natural and problematic, for, the ‘[e]arly gentrifiers’ narrative of the neighborhood, its cultures, and its communities is flawed in the sense that it largely excludes the narratives of other groups and contains several internal contradictions’ (2011, p. 307). Following this argument, it is not surprising that the East Village early gentrifiers were unable to turn their nostalgia narrative into effective action, nor that they could not prevent the ultimate displacement of themselves and other residents. They were, however, perhaps able to the use their nostalgia narrative to influence the behaviour of some people in the area (predominantly, in this case, other politically-minded artists). Nevertheless, anti-gentrification art, with its ‘urban blight’ aesthetic, helped sell East Village as ‘a new bohemia’ which, in turn, encouraged new investment in commercial service enterprises, including art galleries (Martinez, 2010, p. 18). This was later echoed by Sholette:

An incoming wave of young, white professionals, many of whose parents had fled the inner city for suburbia years earlier, moved to low-rent neighborhoods within close commuting distance from Wall Street. Like the shock troops of a new, ‘creative’ working class, these incoming ‘gentry’ absorbed and regurgitated the dissident culture they found in the city—including rap, hip-hop, graffiti, street art and break dancing—while simultaneously, though largely inadvertently, driving up rents, and pushing out poor and working-class residents (2011, p. 64).

It would appear then that the use of artists in Lower East Side to smooth the gentrification of the area reflected the beginnings of a coordinated approach in which city authorities, corporate interests and culture forged new links that would become the blueprint for future gentrification initiatives on a global scale. Anti-gentrification art proved, in this case, to be easily appropriated by this new coordinated alliance as ‘a niche-market indicator’ grounded by its ‘culture of insurgency’ (Mele, 2005 [1996], pp. 314, author's italics).[14] The galleries provided international connections and marketing, whilst the street art provided a constant visual indicator of the neighbourhood’s ‘edgy’ culture. Indeed, by the start of 1985, the ‘East Village Scene’ was described as a ‘howling success’, with more than sixty galleries open in the neighbourhood. For Glueck, East Village provided a heady mix that was clearly ripe for exploitation:

[W]ith its mean streets and dingy clubs still providing a sense of adventure, it's the place to show, go and be seen. So hot, in fact, is this artists' milieu, many of whose more-or-less improvisatory galleries are themselves artist-run, that it's taken on the dimensions of a Movement (Glueck, 1985).

Indeed today, the Lower East Side is considered ‘the largest, highest-quality, and most vibrant downtown art community the city has ever seen’, although many galleries may be forced to move soon due to rising rent costs (Lesser, 2016).

It is therefore little surprise that at the borders of the privileged, elitist, superficial and fiercely policed playground of today’s art world lurk the New Bohemias and New Bohemians, just waiting to be ‘discovered’. And it is unsurprising that this art world is wrapped, cloak-like, around its bastard siblings, the property world and the economic world. The New Bohemians – and this includes street artists - are precarity’s perfectly imperfect role models. They are flexible, adaptable, creative, seemingly unique – authentic. And it is just such characteristics that make them such a pliable vanguard for the Creative Class and gentrification. This is because the New Bohemians, unlike the Old Bohemians, are out-and-out capitalists.

The Creative Class is a capitalist class. Bigger PR and advertising agencies, tech companies, music companies and musicians, new media-makers, architects and, of course, arts organisations and established artists, when moulded together en-masse, become the stalwarts of the Creative Industries and its forerunners – its colonising pioneers.

Venture capital and crowdfunded start-ups cluster micro-enterprises in and around New Bohemias, hoovering up any authenticity in the name of taste, urban living and individualistic style. They are joined in this aesthetic feeding frenzy by legions of tattooists, pop-up foodie stops, fancy bread bakers, posh tea and coffee places, up-cyclers, micro-brewers – the list is almost infinite. And it is the arrival of the hipsters, bobos and fashionistas that signals the end for a city’s marginalised people and its peripheral places, but not the ‘struggling’ artists. Creativity becomes what I term ‘uncreative creativity’: the formulaic corporate consumerism of our current ultra-neoliberal capitalist system.

Using aesthetics to redefine certain areas of cities as being desirable is ‘an act of class power’ (Bridge, 2001). It brings middle-class culture in the guise of bohemians, artists, hipsters and tech entrepreneurs – lumped together today as the creative class – into direct, day-to-day contact and conflict with working-class cultures and histories. The aestheticisation of working-class areas opens the door for the middle-class to claim or reclaim neighbourhoods, doing-up properties in the name of gentrification and in the hope climbing the property ladder by kick-starting the property price elevator.

Of course, the gentrifying waves of artists, hipsters, creatives, tech start-ups and bankers all share a common (re)vision of the working-class lives that preceded them. Romanticised, idyllic, sentimental and nostalgic, they remake ex-working-class places in grotesque, ironic parodies and pastiches of past lives and past struggles. In other words, they exploit them.

Richard Lloyd describes these temporal places as ‘neo-bohemias’ – conduits between artists and commercial investment. Predominantly white, well-educated, professional and interesting in living like artists, the neo-bohemians – led by what Lloyd describes as ‘aspiring artists and hipster hangers-on’ - are proficient at displacing lower-income and ethnic minority residents (2006). Being ‘hip’ is, of course, an essential element of enterprise (Frank, 1997) and late-capitalism happily munches on its margins - on marginal people and marginalised cultures. Capitalism first mimics then consumes the ‘cool’. This inevitably led to the bohemian lifestyle becoming fused with the bourgeois lifestyle to create the hybrid form known as bobos – the bourgeois bohemians (Brooks, 2000).

It is this hybridisation which enabled the commodification of artists, setting them free to ride on gentrification’s rising tide whilst simultaneously shackling them to the yoke of the creative industries. Similarly, this stylistic hybridisation led to the creation of today’s incarnation of the hipster: bereft of the originalities and anti-establishment ethos of previous generations of hipsters; dependent on rampant (if supposedly “micro”) entrepreneurialism, shallow pastiche and unapologetic kitsch.

But, unlike hipsters, artists are the advance troops of gentrification. They create outposts for future gentrification that lie beyond the gentrification frontiers. First come the artists, the writers, then the ‘creatives’, then come the hipsters. Their target: areas where property is cheap, preferably near cultural venues and places with a ‘history’ – places, in other words, where lower-income people live. They rent places and tidy them up or buy places and renovate them. They open new artists’ studios, art galleries, bijou shops. They get involved in local governance and politics. Rents and property prices rise. Long-time, local shops, cafés and pubs close, rapidly replaced by newer, nicer ones. Old business-owners replaced by new, old staff likewise, the area changes quickly – almost before the eyes of disbelieving residents. Trendy visitors come to the area in search of the new. They go on street art tours. Some of them covet a place there too. They rent or buy, joining the throng. The artists, writers, creatives, hipsters and trendy middle-class followers begin displacing lower-income people, poorer communities.

Then come the businesspeople, bankers, teachers – the established, ‘respectable’ middle-classes. Property prices rise again, rise further. More and more of the lower-income people and small businesses are forced to leave their homes. They can’t afford the rent. They’re tempted by making a profit on the property they own by selling it at the new prices but will have to move elsewhere to buy their next home. They’ve lost their jobs. They’ve lost customers and trade. Friends, family and whole communities have left: moved on; dispersed. They no longer fit in. They are no longer wanted. They must go. Now! They leave. Replaced by new people, New shops, restaurants, bars. The area has changed. The libraries and other public buildings have been closed or ‘saved’ by a heady mix of middle-class voluntarism and crafty asset transfers. The area is middle-class, trendy. The area has been gentrified.

But who makes the places for the ‘placemakers’ – the New Bohemias for the New Bohemians? Not the artists nor the writers nor the creatives nor the hipsters. Not the studio and gallery owners. Not even the teachers, businesspeople nor the bankers. The New Bohemias begin life as ‘zones’ – re-zoned zones. State and local authorities listen to financial investors and property developers then together they map out regeneration zones or ‘opportunity areas’.

This process takes place many years ahead of gentrification. First, the area – its people, places, businesses, homes – suffer planned disinvestment. They are quickly labelled no-go-zones, ghettos, slums, sink estates – failing. They are made to fail. And failing places are beacons for the pioneering artists, writers and creatives who themselves act as beacons for the hipsters and their coteries.

Then come announcements, often in quick succession. Regeneration. Renewal. New investments. Not for the existing population. Not for many existing places and buildings. Not for what’s there already. New investments for new things. New zones with new transport links. First come art galleries, cultural centres, museums and artist studios. Then developers announce the refurbishment of listed and regeneration-worthy buildings, ‘breathing new life’ into the deliberately delipidated shells. New shops and retail spaces literally ‘pop-up’ – the precursors of permanent developments. More temporary studios and micro-businesses erupt. Mass demolitions and ‘repurposing’ of social housing. New build, mixed-use developments. New public spaces that are, in fact, sanitised private spaces. Property prices and rental values rise and rise. Newspapers and magazines write about these newly ‘up-and-coming’ places, accelerating gentrification: cheaper than already gentrified neighbourhoods; ‘edgy’, ‘happening’, ‘cool’, ‘hip’.

It’s the planned disinvestment and regeneration cycle that drives gentrification. The authorities sell-off their buildings and land to property developers, offering them subsidies, streamlined planning applications, tax breaks, infrastructure investment, “improved” neighbourhood policing, draconian penalties for homelessness, more. They redraw the city maps, colouring in wave after wave of kept-secret (unless you’re in-the-know) new ‘opportunity areas’. Artists and hipsters pave the way with the increasingly short-lived, ‘meanwhile’ utopias: New Bohemias with incredibly short lifespans. But that’s exactly their function. That’s the point. Much more transient than previous Bohemias, New Bohemias literally mirror the nomadic lifestyle from which the name Bohemian derives. Here today, gone tomorrow. Not gone – just moved on, New Bohemias are the frontline of gentrification.

The New Bohemians know their role. Their protests at being moved on or priced-out of their latest meanwhile spaces are always shallow, always false. They knew these, just like the ones before and the ones that will follow, were temporary arrangements – short-term ‘opportunities’. Like a pack of Littlest Hobos, they just keep moving on.

So, art (and that includes street art) and gentrification go hand-in-glove because gentrification merges the economic value of space with the cultural value of heritage and the arts, mediating these values through the lens of aesthetics and the histories of art and architecture (Zukin, 1991). Cultural production and consumption therefore become drivers for economic growth. This enables the cultural values of individual places to be extracted and packaged as part of the ever-expanding (and, paradoxically, thereby narrowing) homogeneous culture of the global marketplace.

Gentrification has become the Global Urban Strategy, driven by two factors: the neoliberal state absolving itself of its responsibilities as the regulator of capitalism to act as the ultimate agent of the free market; and a massively upscaled, thoroughly generalised gentrification process (Smith, 2002). For Smith, this strategy usurped social reproduction, replacing it with capitalist production on a global scale. Crucially, as the now dominant global urban strategy, gentrification is intimately connected to global capital and cultural production, distribution and consumption.

The process wipes clean entire areas, communities, classes, ethnicities, announcing their erasure with a heady mix of glass-fronted luxury apartments, repurposed ex-public service buildings, community festivals, flamboyant art spectaculars and huge new citadels for the celebration of white, middle-class culture: art galleries, opera houses, theatres. Many of these hugely expensive artistic behemoths wryly wink at their neighbourhoods’ working-class heritage – falsely nostalgic; fake sentiments.

Yet, one area that is often overlooked is the extent to which many of us are gentrifiers too. I’m the first to admit that I’m a gentrifier. Perhaps that’s the final irony of gentrification: Everyone’s A Gentrifier Nowadays. (Well, everyone who is relatively well-off or possessing reasonable amounts of cultural capital.) We are subjected to what John Joe Schlichtman and Jason Patch described as six interrelated pull factors: economic – affordability of housing, future value of (owned) housing and cost of living; practical – closeness to city centre and key facilities and larger houses; aesthetic – the appeal of architectural significance and its renovation; amenity – closeness to schools, parks, galleries, museums, shops, restaurants, cafés, etc.; social – diversity and a sense of community; and symbolic – the sense of ‘restoring’ and ‘saving’ a struggling community (Jane Jacobs did this – first in Greenwich Village; then in Toronto), maintaining its ‘heritage’ and its ‘authenticity’ (2014).

Does this sound familiar? Much of it rings true about my life choices. Of course, it is also common for gentrifiers to settle-down, moving from gentrifying or newly gentrified neighbourhoods to traditional middle-class areas in search of good schools and gardens for their children.

But are the middle-classes or creative class in some way trapped in their roles as gentrifiers? Is, as Schlichtman and Patch wondered, the only hope for middle-class people in gentrifying areas either to get out to the suburbs (and become a different kind of stigmatised entity) or to stay and help the working-classes and ‘indigenous’ people maintain their heritage, their authenticity (2014)? Is it now unethical for the middle-classes to try to live ethically, to care about living together within diverse communities? Likewise, it is unlikely that all art undertaken in gentrifying areas by anyone remotely middle-class or part of the creative class (i.e. an artist) will to contribute towards gentrification and the displacement of ‘authentic’ residents.

It is perhaps time then to realise that classes must be able to live and work together – not in segregation. It is important to realise that class dynamics can be incredibly divisive and increasingly difficult to reconcile, but it is equally important to understand that class dynamics can be a force for positive change: for social justice, equity and fairness; for community. It is only when middle-class people or artists exploit their situations, their privileges, their (relative) freedoms that other people are exploited. Perhaps, then, the notion of all middle-class people and artists as gentrifiers is unhelpful – an unfair oversimplification at best, a demonising slur at worst?

So, what does all this have to do with street art? Well, street art plays an integral part in all this. It has moved from being an activist practice with radical hopes and dreams for a radically different future to an artistic practice that is at once integral to today’s art world, property world, economic world; in short, part of the Creative City and Creative Class narratives that merge nostalgic pasts with shiny new futures – an integral part of the global neoliberal capitalist hegemony.

Festivals and walking tours, museums and glossy magazines, Instagrammable images and big money values, mystery and accessibility – street art is, just like everything in our hyper-commodified Western lives, complicit in the perpetuation of capitalism. And, street art is part of the problem, not the solution. It was appropriated and recuperated too easily a long time ago. We must now find new ways of challenging the oppressive chains of all-encompassing capitalism. For, just as there’s more today than yesterday, you can guarantee that, under neoliberalism, it will be less than there’ll be tomorrow. Until, that is, we wake up our own contraries and our own collective agencies.

THANK YOU.

Bibliography

Abarca, J., 2016. From street art to murals: what have we lost?. Street Art and Urban Creativity Scientific Journal, 2(2), pp. 60-7.

Anderson, M., 1983. AHOP: The First Battle. UPFRONT, Issue 6-7, p. 4.

Bridge, G., 2001. Bourdieu, rational action and the time-space strategy of gentrification. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Issue 26, pp. 205-16.

Brooks, D., 2000. Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There. New York: Touchstone.

Frank, T., 1997. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Garber, S., 1984. Where Goes the Neighborhood? Not For Sale, The East Village Art Scene, and The Lower East Side. UPFRONT, Issue 9, pp. 13-16.

Glueck, G., 1985. GALLERY VIEW; EAST VILLAGE GETS ON THE FAST TRACK. [Online]

Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1985/01/13/arts/gallery-view-east-village-gets-on-the-fast-track.html

[Accessed 6th January 2017].

Hansen, S., 2015. ‘This is not a Banksy!’: street art as aesthetic protest. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, pp. 1-15.

Hobsbawm, E. & Ranger, T., 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hornung, S., 2014. Artists and Gentrification: Don't Let Action Dissolve into Discourse. [Online]

Available at: http://www.artslant.com/9/articles/show/38542

[Accessed 18th November 2015 2015].

Inspiring City, 2014. Street Artists Boe & Irony Paint a Giant Chihuahua on Chrisp Street in East London. [Online]

Available at: https://inspiringcity.com/2014/06/22/street-artists-boe-irony-paint-a-giant-chihuahua-on-chrisp-street-in-east-london

[Accessed 5th August 2019].

Lees, L., 2003. Super-gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City. Urban Studies, 40(12), p. 2487–2509.

Lesser, C., 2016. Why New York’s Most Important Art District Is Now the Lower East Side. [Online]

Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-why-new-york-s-most-important-art-district-is-now-the-lower-east-side

[Accessed 6th January 2017].

Lloyd, R., 2006. Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City. First ed. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

Martinez, M. J., 2010. Power at the Roots: Gentrification, Community Gardens, and the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side. Lanham and Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Mele, C., 2005 [1996]. Globalization, Culture and Neighborhood Change. In: J. Lin & C. Mele, eds. The Urban Sociology Reader. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 308-316.

Morgan, T., 2014. Art in the 1980s: The Forgotten History of PAD/D. [Online]

Available at: http://hyperallergic.com/117621/art-in-the-1980s-the-forgotten-history-of-padd/

[Accessed 3rd January 2017].

Ocejo, R. E., 2011. The Early Gentrifier: Weaving a Nostalgia Narrative on the Lower East Side. City and Community, 10(3), pp. 285-310.

PAD/D, 1981. PAD: Waking Up In NYC. UPFRONT, Issue 1, pp. 1-4.

Polland, J., 2012. See Why London's East End Is One Of The City's Hottest Areas. [Online]

Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/explore-the-stylish-neighborhoods-of-east-london-2012-8

[Accessed 5th August 2019].

Pritchard, S., 2017. Artwashing: The Art of Regeneration, Social Capital and Anti-Gentrification Activism, Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Northumbria.

Pritchard, S., 2018. New Bohemias. [Online]

Available at: colouringinculture.org/blog/newbohemiasintro

[Accessed 5th August 2019].

Rea, N., 2019. Street Art Is a Global Commercial Juggernaut With a Diverse Audience. Why Don’t Museums Know What to Do With It?. [Online]

Available at: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/street-art-museums-1617037

[Accessed 12th August 2019].

Reed, M., 2018. Space is the Place. Nuart Journal, 1(1), pp. 3-6.

Schacter, R., 2014. The ugly truth: Street Art, Graffiti and the Creative City. Art and the Public Sphere, 3(2), pp. 161-76.

Schlichtman, J. J. & Patch, J., 2014. Gentrifier? Who, Me? Interrogating the Gentrifier in the Mirror. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), pp. 1491-1508.

Schumpeter, J., 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Seymour, B., 2004. Shoreditch and the creative destruction of the inner city. Variant, Volume 34.

Sholette, G., 1997. Nature as an Icon of Urban Resistance: Artists, Gentrification and New York City's Lower East Side, 1979-1984. Afterimage, 5(2).

Sholette, G., 2011. Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. London and New York: Pluto Press.

Sholette, G., 2014. A COLLECTOGRAPHY OF PAD/D Political Art Documentation and Distribution: A 1980’s Activist Art and Networking Collective. [Online]

Available at: http://www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/14_collectography1.pdf

[Accessed 4th January 2016].

Sholette, G., 2016a. Audio Interference 16: Greg Sholette [Interview] (March 2016a).

Sholette, G., 2016b. Sholette’s Art Estate presentation for Martha Rosler’s exhibition If You Can’t Afford To Live Here MO-O-OVE! June 14, 2016. [Online]

Available at: http://gregsholette.tumblr.com/post/145973861995/sholettes-art-estate-presentation-for-martha

[Accessed 5th January 2017].

Smith, N., 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. London: Routledge.

Smith, N., 2002. New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy. Antipode, 34(3), pp. 427-50.

Zukin, S., 1991. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zukin, S., 2011. Public Art: Tracing the Life Cycle of New York’s Creative Districts. Osaka, Urban Research Plaza, Osaka City University.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Giant Chihuahua Gentrified!, Boe & Irony, 2014. Photograph @David Wormley.

Lower East Side Anti-gentrification stencil art, PAD/D. 1984. Photograph @PAD/D.

Out of Place, PAD/D, 1984. Photograph @PAD/D.

Not For Sale, PAD/D, 1983. Photograph @PAD/D.

Not For Sale 2, 1983, PAD/D. Photograph @PAD/D.

Leith Boundary Bier Hoose Shutter Art, LeithLate, 2018. Photograph @Stephen Pritchard.

IT’S NOT TOO LATE…, LeithLate, 2018. Photograph @Stephen Pritchard.

[1] Interestingly, Zukin reveals that when urbanist Jane Jacobs was living in Greenwich Village, ‘rents were already much higher than in the rest of Manhattan’ (2011, p. 29).

[2] The area of Bushwick is currently experiencing the pressures of gentrification. Artists resisting gentrification there are discussed in the next section.

[3] Neil Smith, for example, described the appropriation of sub-cultures as follows: ‘graffiti came off the trains and into the galleries, while the most outrageous punk and new-wave styles moved rapidly from the streets to full-page advertisements in the New York Times’ (1996, p. 17).

[4] In the first issue of UPFRONT, the collective’s publication, PAD/D described itself as follows: ‘PAD (Political Art Documentation/ Distribution) is an artists’ resource and networking organisation coming out of and into New York City. Our main goal is to provide artists with an organized relationship to society; one way we are doing this is by building a collection of documentation of international socially-concerned art. PAD defines “social concern” in the broadest sense, as any work that deals with issues … Historically, political or social-change artists have been denied mainstream coverage and our interaction has been limited … We have to know what we are doing … The development of an effective oppositional culture depends on communication.’ (1981, p. 1).

[5] Indeed, Sholette went on to describe the Lower East Side as follows: ‘Overturned cars, their chassis stripped of parts, were strewn along the sides of streets … Burnt out or demolished properties cut spaces between tenement buildings. These openings became filled with rubble, trashed appliances, syringes and condoms, as well as pigeons and rats. Often they appeared to be returning to a state of wilderness as weeds and fast-growing ailanthus trees began to sprout from the piles of fallen bricks and mortar. Along some stretches of these avenues there were more square feet of this antediluvian scenery than extant architecture’ (1997).

[6] Sholette described this ‘mongrel thing’ as follows: ‘[R]esidents in this predominantly Latino community could be seen organizing gardens amid the rubble and entering and leaving tenements to go to work, always outside the neighborhood, to shop or to visit social dubs. In the summer Ukrainian men played checkers in Thompkins Square, while the women sat together on the opposite side of the park conversing. Black leather and mohawks, remnants from the already fading punk scene, shared sidewalks with kids chilling in open hydrants. There was always the sound of a conga drum, meting out a near 24-hour pulse’ (1997).

[7] Which he described as ‘a ticket out of the East Village for the lucky few’ (Sholette, 1997).

[8] Nostalgia is often employed by early gentrifiers, such as artists, to create a ‘new local identity’ that stakes a claim to ownership (along with or in place of existing residents) of an area. Ocejo called this the ‘nostalgia narrative’ (2011, p. 286). Although, it is also possible this is unfair and instead the result of Sholette being by far the most prominent voice on the history of PAD/D.

[9] The initial exhibition comprised of two hundred art works.

[10] Leona Helmsley was a notorious gentrifier who turned loft spaces into luxury condominiums.

[11] For example, Sholette wrote in 2014 that: ‘[A]s a means of repelling gentrification or of establishing an alternative realm of artistic practice [PAD/D] did not succeed. Yet the emergence of tactical media and new forms of collectivism over the past ten years suggest the possibility of establishing a counter-hegemonic, cultural sphere is not a linear process, just as the historical re-construction of groups such as PAD/D is part of a re-mapping that ultimately leads to questions about the nature of creative, political resistance itself’ (p. 12).

[12] Ocejo describes commercial gentrification as the expansion of ‘new establishments with particular goods and services - such as clothing boutiques, art galleries, cafes, restaurants, and bars - that open to satisfy the needs of middle-class gentrifiers’ which leads to ‘social and cultural displacement for existing residents as new businesses attract new uses and users to the neighborhood’ (2011, p. 285).

[13] Miranda Martinez described the early artist gentrifier aesthetic based upon existing urban detritus as follows: ‘The decimation of so much housing along with the steep decline in population of the Lower East Side created the preconditions for the gentrification of the 1980s. As young artists arrived during the early stage of gentrification, they created a localized art movement that celebrated the Lower East Side ghetto environment as an aesthetic’ (2010, p. 18).

[14] Sociologist Christopher Mele described how East Village’s ‘culture of insurgency’ was used to promote the neighbourhood as resistant to mainstream society and culture, creating what he described as ‘the downtown genre’ which fuelled the expansion of new art galleries showing work from this genre (2005 [1996], p. 314).